Food Waste or Warmth: Supermarket Donations in Japan and the Netherlands

I’ve read about a supermarket in the Netherlands giving away leftover bread to a food bank!

I wish we could do that easily in Japanese supermarkets too…by changing consumer attitudes.

Maybe their systems are also different… but either way, it’s nice when food finds people, not trash bins :))

Food waste is a global issue, but the way each country deals with it reflects its culture and social structure.

In this post, let’s dig deeper into how supermarkets in the Netherlands and Japan are turning food loss into sharing!

Food Sharing at Dutch Supermarkets

DutchVoedselbank (food bank): How donation works

In the Netherlands, voedselbanken Houten (=food banks) Nederland operates more than 200 branches nationwide, redistributing surplus food from supermarkets to around 100,000 households weekly.

Major supermarket chains (e.g., Albert Heijn, Jumbo) regularly donate unsold or expiring food such as bread, vegetables, and condiments.

Although the 2023 article by DutchNews reports that surplus donations by supermarkets fell by 20% due to improved efficiency, Voedselbank Nederland still plays a pivotal role in both helping people in need and reducing food waste.

Below is a YouTube video from Voedeselbank Nederland. The video is in Dutch, but it allows you to visualize what it’s like.

I’ve seen it taking place at Albert Heijn once during my exchange year in the Netherlands.

Why is it possible?

There seem to be several factors that allow such well-organized food sharing to work. Here are five primary reasons, in my opinion.

- Governmental and political commitment

- The Dutch government commits to halving food waste by 2030.

- Clear-cut EU guidelines for food distribution

- EU Food Donation Guidelines define safety, labeling, and liability standards, giving retailers confidence to donate safely.

- Public Awareness

- Food Waste Free United ― a nationwide campaign against food waste― has promoted collaboration across retailers and consumers since 2018.

- Logistics and efficiency in retail distribution

- According to a report from Wageningen University, Dutch supermarkets succeeded in cutting down on food waste by approx. 35 % (2018 – 2024) through improved distribution systems such as donations.

- This achievement is likely to boost the momentum of food donation.

- Community collaboration and trust

- Voedselbank Houten in Nederland argues that their thriving attributes to cooperation between the government, supermarkets, and volunteers… supported by shared trust in each other rather than strict legal force.

Although challenges remain in the Netherlands, it’s impressive to make such a nationwide sharing function!

Then…what about Japan?

What About Japanese Supermarkets?

Overview: food waste in Japan

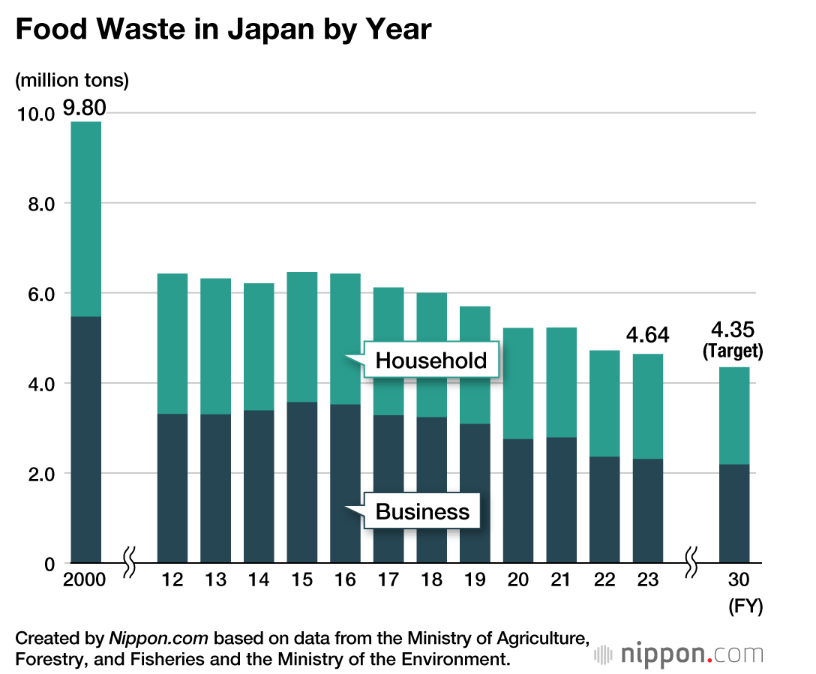

As of fiscal year 2023, Japan generates around 4.64 million tons of food waste per year, roughly equivalent to 37 kg per person.

37 kg means… every Japanese citizen wastes the equivalent weight of 250 onigiri (rice balls).

250 of us thrown away!? OMGggg

Despite the Japanese government’s statement to halve food waste by 2030 compared to 2000, progress has been slight, as shown below.

Why supermarkets matter

As indicated in the graph above, around half of the total waste amount comes from the food industry, including retail. (The other half is from households.)

And needless to say, supermarkets are the go-to retailers for many of us. That’s why supermarkets play a central role in the food waste discussion.

Why food sharing is hard in Japan

But what makes it so difficult for Japanese grocery stores to engage in donating goods that are otherwise wasted?

From my viewpoint, there are mainly four obstacles.

[1] Strict retail regulation (“One-third Rule”)

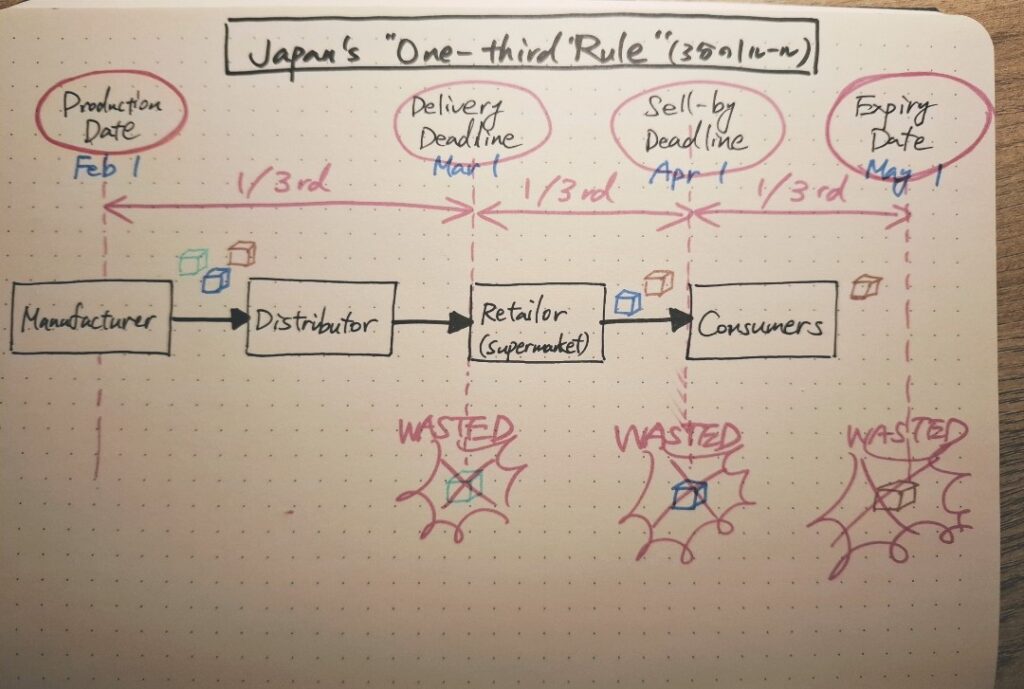

Let’s say you are a distributor. You received a set of new items from manufacturers, whose production date is Feb 1 and whose expiry date is May 1.

According to Japan’s “One-third Rule,” you must have the items delivered to retailers by Mar 1. Likewise, retailers must sell them by Apr 1. (Look at the figure below.)

Here’s the thing: if the items pass one day past the 1/3 deadline, they need to be disposed of…

Such a short inventory regulation― shorter than other nations like the US (1/2nd) and the UK (3/4nd) ― causes premature disposal of edible food.

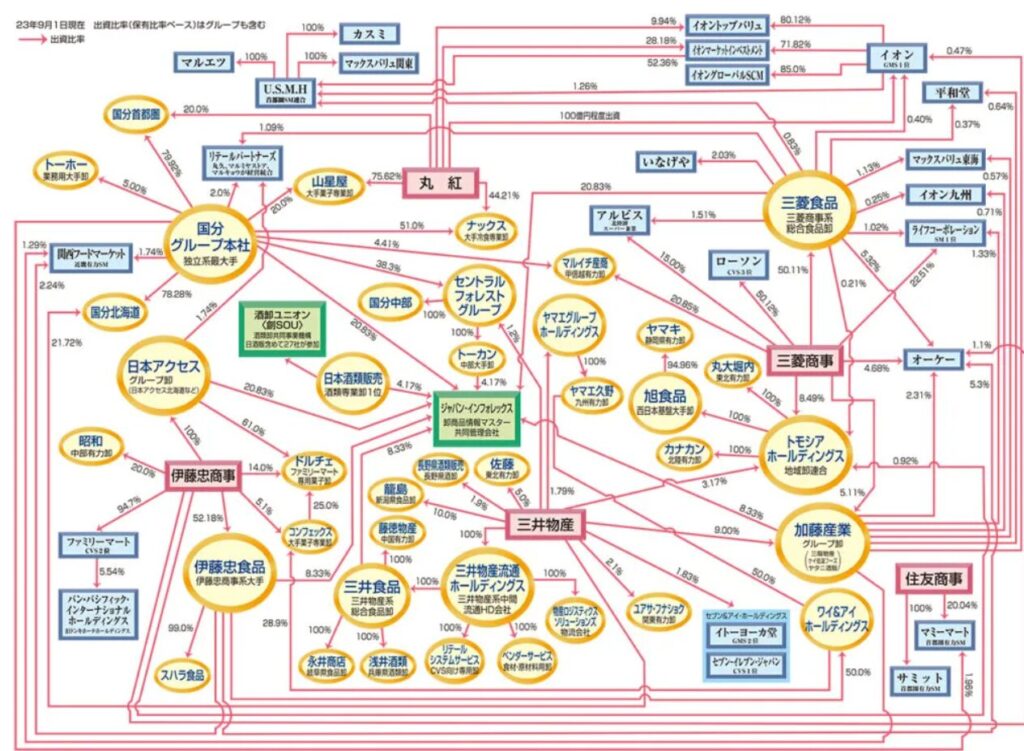

[2] Complex supply chains

Before arriving at supermarkets, food products go through multi-layered intermediaries (e.g., JA Cooperatives, logistics hubs, and several distributors). As someone working in multiple food sectors in Japan, I know this first-hand: yes, very complicated networks like the figure below…

That’s why it’s not easy to make logistical changes in collecting, storing, and redistributing surplus food in the whole supply chain.

[3] Defective policies & corporate risk aversion

In 2019, the Act for Promoting Food Waste Reduction was enacted by the Japanese government. But unfortunately, it entails no punishment for breaching its policies.

Companies often prioritize brand safety over sustainability when regulations are ambiguous. Without strong incentives (like rewards or punishments), they are likely to avoid actions with potential reputational risk.

- [4] High consumer demands for appearance and cleanliness

- This one is more of a cultural factor: Japanese customers tend to prioritize aesthetics and cleanliness, which leads manufacturers and retailers to offer only “perfect” items without any scratches and dents.

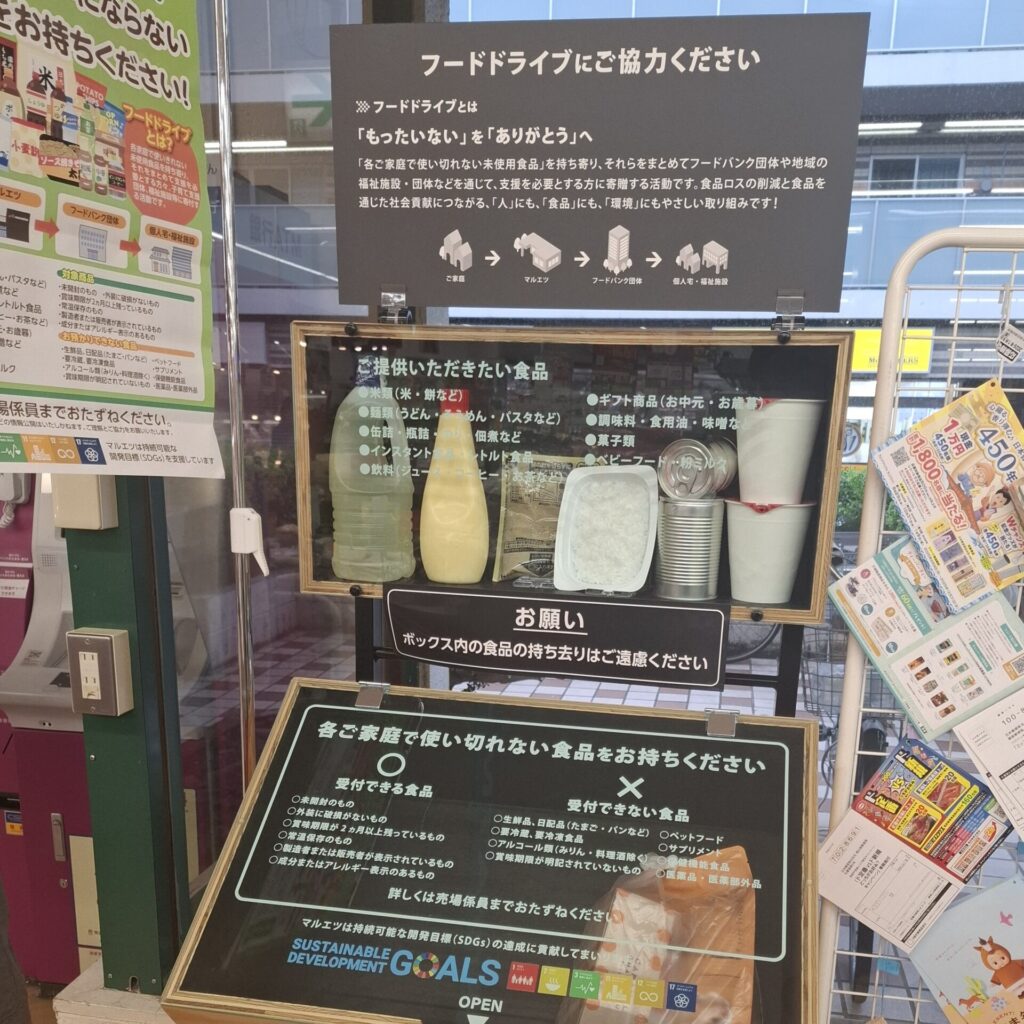

A sliver lining in Japan

Maruetsu ― a Tokyo-based supermarket chain ― has installed in-store collection boxes for food drives, where consumers can donate unopened, non-perishable food from home. The collected items are delivered to local food banks such as NPO Lion Heart and Second Harvest Japan.

My Opinion and Experiences

Although collection boxes at supermarkets are a progress, I think multiple challenges remain in Japan: Unlike Voedselbank Nederland, Japan’s food drives do not accept perishable fresh food (e.g., bread, vegetables, and dairy) for fear of food safety and hygiene. Moreover, surplus food for donations must be from households, not from retail supply chains.

For this, it’s not systematized, remaining highly dependent on voluntary actions by consumers. I don’t know if such donations outside of the mainstream retail logistics are really effective and sustainable in the grand scheme of things.

By the way, when I was working for a Japanese supermarket, taking expired food home was strictly prohibited, mainly for fear of corporate risks with safety concerns… so, the arguments above resonate with me.

Summary

Supermarket Food Donations: Netherlands vs Japan

| Cleanliness, appearance, and safety. | Netherlands | Japan |

|---|---|---|

| Main System | Nationwide food bank, associated with supermarkets | Mostly by regional NPOs (No nationwide systems) |

| National & Corporate Attitudes | Strong collaboration supported by EU guidelines and national targets | Weak policy enforcement without incentives → companies remain risk-averse |

| Consumer Attitude | High awareness of food waste and sustainability | Cleanliness, appearance, and safety |

| Challenges | Managing consistent supply and logistics | “One-third rule,” complicated supply chains, and strict food-safety culture and expectations |

Though their paths differ, both countries are heading in the same direction: transforming food waste into warmth by giving it a second life.

Right. As seen in the case of food banks, what would otherwise be discarded can become a source of connection and love.

What do you think? Let me know in the comments below!

Your words make my day!